The dark history behind Brisbane street name

The brutal history of Europe’s colonisation of Australia has left enduring marks on the nation – some still visible, others far less so.

Among the reminders of these times are the innocuously-named Boundary Streets on the southern and northern edge’s of Brisbane’s city, in West End and Spring Hill respectively.

“I learnt about this a number of years ago and have always been slightly horrified,” a Queensland woman wrote on Facebook this week.

While some Queenslanders understood the meaning behind the name, many who commented on the widely shared post admitted they did not.

The streets mark the spot of a bygone perimeter on the edge of town where indigenous and other non-white people were not permitted to enter during the evenings and on Sundays.

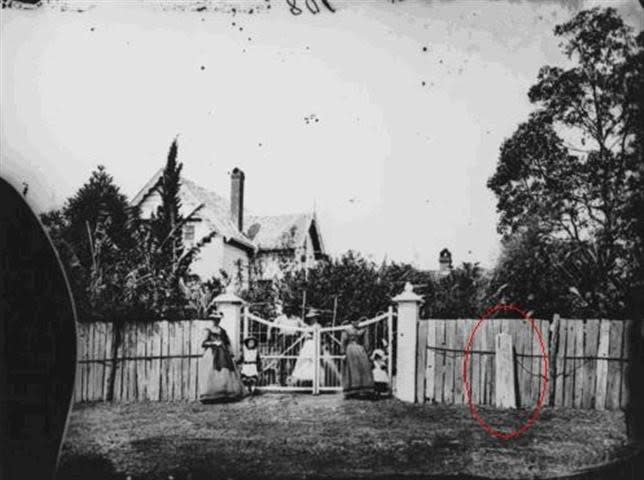

The racial borders were common in Queensland settlements and were typically displayed by a wooden post, known as boundary posts.

“Mounted troopers would ride about Brisbane after 4pm cracking stockwhips as a signal for Aborigines to leave town,” notes one historical recounting of the boundary posts being enforced.

Aboriginals excluded from townships after 4pm

The emergence of the formal segregation was explained in Brisbane: The Aboriginal presence 1824-1860, edited by Rod Fischer.

“For whites in Queensland's colonial towns, the problem remained of keeping Aborigines at a sufficient distance to contain them as a perceived social and moral liability, whilst maintaining them near enough, as a cheap expendable labour force,” it said.

“In solving this problem the metropolitan police became a vital ingredient – allowing Aborigines into the township for desultory and dirty labour by day, then driving them out at 'curfew' times each evening.”

The blanket exclusion of Aboriginal people through border curfews was largely a Queensland practice, says historian and author of True Gurt, David Hunt.

“It certainly wasn’t used widely throughout Australia,” he told Yahoo News Australia. “Queensland has a more vexed racial history.”

In other settlements like Van Diemen's Land, now Tasmania, indigenous people who didn’t live in the townships would still be forced out after certain times but not those working in town as servants.

“In Van Diemen's Land the law tended to apply to Aboriginal people who were not already living in the city – the ‘tribal blacks’ rather than the ‘house blacks’,” he said.

While the bounday posts are thought to have popped up around the 1840s, after Brisbane was settled as a penal colony in the 1820s, the discrimination continued long after policing of the curfew waned.

“Throughout Australia, even where Aboriginal people entered towns, they would have been refused service in bars, shops, hairdressers,” Mr Hunt said.

Those forms of exclusion, from businesses and public places like swimming pools, “lasted well into the 1960s”.

‘Changing the name wouldn’t change history’

In 2016, there was a push to change the name of Brisbane’s Boundary Streets, but it’s not an idea that is necessarily endorsed by the indigenous community.

Then Lord Mayor Graham Quirk reportedly considered changing the street names, potentially to Boundless Street after they were changed by a street artist.

“Changing the name wouldn’t change history,” says Aunty Heather Castledine, a community elder and co-chair of Reconciliation Queensland Incorporated.

“But it’s acknowledging it and letting people know, this is what happened,” she told Yahoo News Australia.

“This is part of the history of this colony.”

In August, Ms Castledine led a walk from Boundary Street to Boundary Street in the Brisbane city to raise awareness of the historical significance embedded in the name. It’s something she began the year after the national apology to the stolen generation by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2008.

“If people were told about it and [you] let them know, it would make a big difference,” she said. “But when you don’t know how can you change it?”

The walk is about “not letting it become a hidden history.”

Debate rages over ‘whitewashing’

Racial inequality, stemming from an uncomfortable history of slavery and oppression in centuries gone by, has been thrust into the public consciousness as the Black Lives Matter movement surges in cities around the world.

Across the US and Europe, as well as in New Zealand, the anti-racist protests have resulted in the removal of a number of statues depicting historical figures due to their links to slavery.

It has sparked heated debate, one that has also seen media companies remove content now deemed too racially insensitive.

But when it comes to something like renaming Brisbane’s Boundary Streets, historian David Hunt thinks it would result in the loss of profound reminders and important historical context.

“I think if you start erasing bits of our history, then people no longer have this sort of segregation in their consciousness,” he said.

“In attempting to whitewash or blackwash the past, you actually erase the knowledge in contemporary Australians that these sorts of incredibly racists policies existed.”

Do you have a story tip? Email: newsroomau@yahoonews.com.

You can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter and download the Yahoo News app from the App Store or Google Play.