40 years on, Thurman Munson's death remains one of sports' most stunning moments

Four decades later, it’s still tough to believe there’s no happy ending to the last Thurman Munson story. No miracles. No one pulled the Yankee captain from the burning wreckage of the Cessna that he crashed in Canton, Ohio, 40 years ago this week. No one talked him out of flying a jet too powerful for him to control. No hero saved his life. No one could.

Instead, Thurman Munson, who died at the age of 32, left behind an array of loved ones doing the best they could amid unthinkable tragedy. A wife who raised three kids without their father. Teammates who can’t forget him four decades later. Friends and fans forced to go on without their moral center, without their captain.

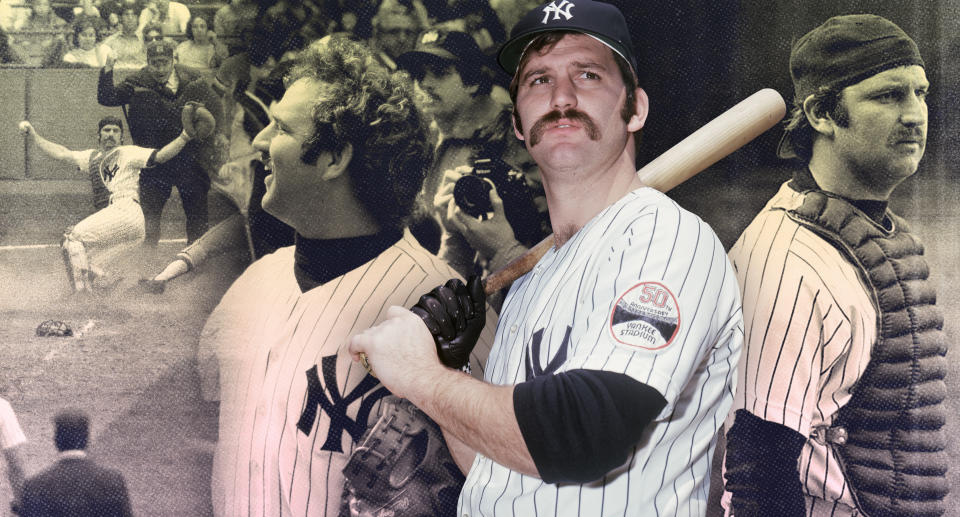

Like Hendrix and Cobain and Belushi, Munson was an outsized presence gone before anyone thought he could be gone. He left behind an orange chest protector, a locker that remains unfilled to this day and stories of how to play ball — stories that have outlived three different Yankee dynasties, stories that ought to last as long as baseball itself.

Granted, the Yankees smother more self-created mythology over the already fog-thick history of baseball than every other team combined. Monument Garden, the pinstripes, banner upon championship banner and number upon retired number — the mandatory reverence gets a little heavy for anyone south of Staten Island.

But in Munson’s case, every bit of that myth-making isn’t just deserved, it's earned and necessary. Munson was the embodiment of every image Yankees fans hold dear. An undersized, oddly shaped catcher — his teammates used to call him “Squatty Body” — he sported a sloppy mustache and a mess of hair, and his uniform always looked like he’d slept in it for three days before the game. He wasn’t slick in his dress or his speech, and he wasn’t a friendly on-camera presence.

What he was, was the lead dog on the most alpha-laden team in the most alpha-obsessed city in the country. The first Yankees captain since Lou Gehrig, Munson was — like Odysseus before him — a reluctant leader, but a natural and a brilliant one.

Too much? In the eyes of Yankees fans, the hero of Homer’s “Odyssey” would be lucky to get compared to Thurman Munson.

“There was never a player that I knew of, on the Yankees or on any other team, who was as respected as much as Munson was on the team,” recalled Moss Klein, who covered the Yankees for the New Jersey Star-Ledger. “I always thought the phrase about being a ‘team leader’ was overdone, but in his case, it was true. The way he played, the way he acted, his toughness … he wasn’t afraid to say anything to anybody. Players gravitated around him. It was really remarkable to watch.”

The time Thurman straightened out Goose Gossage

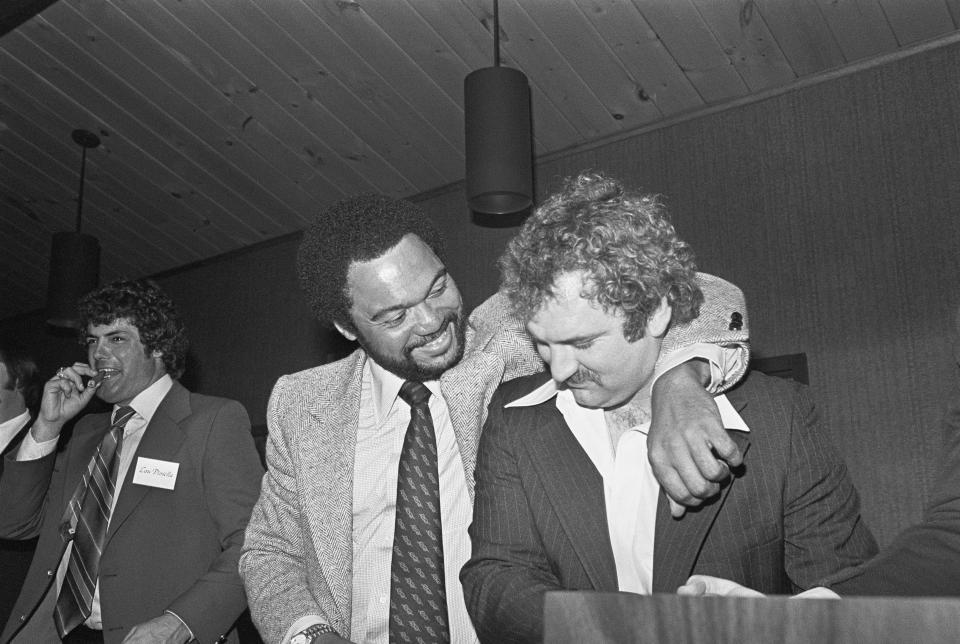

Here’s a Thurman story. April 1978, Toronto. Brand-new Yankee and alleged flame-throwing closer Goose Gossage sat facing his locker, head in his hands. He’d just committed two straight throwing errors in the bottom of the ninth to gift the Blue Jays a win. Which wouldn’t be terrible except for the fact that a week earlier, he’d given up two runs in a tie game against Milwaukee. That gag followed an opening day loss where Gossage had surrendered the game’s only run, a walk-off homer to the Rangers’ Richie Zisk.

Gossage, his face in a towel, kept waving off reporters. Three losses in 11 days. So much for the guy who was going to complement Cy Young-winning Sparky Lyle. Gossage didn’t need to hear the fans to know what they were thinking: You may have been an All-Star in Chicago, buddy, but this is New York. This is the big time. And you’re blowing it.

At some point, though, Munson had seen enough of the silent moping. He walked across the church-still clubhouse, put his hand on Gossage’s shoulder, and said, “Look at it this way, Goose. You’ve lost every possible way you can. It can only get better from here.”

That broke the tension. Munson, who knew exactly how good Goose could be, hauled Gossage out to a steak dinner with himself and Catfish Hunter. And Gossage did indeed get better, finishing 55 games and recording 27 saves in 1978, both league highs. With Gossage back in the pocket, the Yankees would win their second straight world championship.

“Pitchers of that era, when they worked with him, had such confidence in his pitch-calling ability and his ability to run the game from behind the plate,” said Marty Appel, a former Yankees public-relations director and author of a Munson biography. “To a man, whether they were big stars like Catfish or Mel Stottlemyre, or a fringe player just passing through, they all talked about what a treat it was to pitch to Thurman.”

***

By 1979, Munson had been in the league for more than a decade. He’d won Rookie of the Year, MVP in 1976, and two straight world championships. He was one of the top attractions in the Bronx Zoo, willing to go toe-to-toe with manager Billy Martin, superstar Reggie Jackson, or anyone else who crossed his well-defined ethical lines. He was The Captain, and the Big Apple was at his feet. But the crown lay uneasily on his head.

Jackson’s arrival in New York, in particular, set Munson on edge. Although Munson pushed for Steinbrenner to sign Jackson prior to the 1977 season, Jackson lit up the clubhouse with an infamous Sport magazine quote: “This team, it all flows from me. I’m the straw that stirs the drink. Maybe I should say me and Munson, but he can only stir it bad.’’

Jackson would later suggest he was misquoted or taken out of context, but Munson didn’t care for any attempts at backpedaling. As Jackson regaled the media with tales of his own exploits, Munson publicly withdrew. He adopted a Marshawn Lynch-at-the-Super Bowl strategy decades before Lynch, answering “I’m just happy to be here” to any question at any time, until the media gave up and left him alone. He would continue to defend and inspire his teammates, he would continue to orchestrate games like a conductor, but he’d do it without talking to anyone not in pinstripes.

“He was such a central figure on the team,” recalled Klein. “In so many ways he was the main presence in the locker room. Even though he wasn’t talking to writers, it didn’t change his relationship with other players.”

Thanks to the Bronx circus and the pressures of being The Captain, Munson had begun learning to fly. He planned to retreat from New York on off days, back to his wife and kids and hometown of Canton, Ohio. But more than that, he needed the silence, the independence of the cockpit. When he was in the air, no one could touch him. No one could reach him.

For those back on the ground, that was a problem. “Steinbrenner knew about [Munson’s flying], Yankee officials knew about it,” Klein said. “They weren’t happy about it, but they couldn’t do anything about it.”

Flush with both disposable income and deep desire, Munson began a rapid ascent through flight training. He’d been flying for only 18 months and he’d worked his way through three planes, all propellor aircraft. And then, in July, he made a fateful decision: He bought a $1.4 million Cessna Citation, a powerful, blue-pinstriped jet he decorated with the letters N15NY on each side. It was a hell of a plane, quick and muscled, the kind of jet amateurs should only fly in as passengers.

“He was more interested in flying that goddamn plane than he was in playing baseball — to me,” Jackson testified in a deposition in one of the two suits — one filed by the Yankees, one by Munson’s wife — after Munson's death. (The suits targeted Cessna and the flight school where Munson learned to fly. The former suit was dismissed, the latter settled.)

“I just kept telling him, you know, ‘I don’t like to see you flying during the season,’” Martin testified.

Munson saw the Cessna not as a threat, but as a challenge. On August 2, 1979, he had an off day — the Yankees had beaten the White Sox in Chicago the night before; Munson had a strikeout and a walk — and he intended to spend it in his hometown, practicing takeoffs and landings in his new gem.

“He was told that people who own planes like this usually hire pilots to fly them,” Appel said. “It’s a lot of airplane. It’s unforgiving. But Munson was a hardheaded guy, with total self-confidence that he could master anything. For him, it was just, ‘Show me what to do, no problem. I’ll take it up.’”

The time Thurman had to fly commercial

Another Munson story. The Yankees chartered planes as often as they could. But every so often, they’d get stuck flying commercial, and woe to the flight attendants and civilians caught in the vortex.

After a Sunday afternoon Kansas City game, the Yankees ended up booked on a commercial flight to Chicago. The players had enjoyed themselves in the airport bar, and as they boarded the plane and found their seats — in and amongst traveling media and a select few unlucky, unwary fellow travelers — Munson brought the party on board.

He busted out his carryon luggage: a boom box (for those under age 40: a boom box was a huge portable cassette player, the size of a briefcase, with enormous, loud speakers) and began cranking tunes. He’d blast the music, then turn it off, then — right when everyone started to relax — he’d turn it back up again.

Soon enough, Martin sent first base coach Elston Howard — a 6-foot-2 Yankee legend — back to shut Munson up. Munson was unintimidated.

“Are you the music coach now, too?” Munson yapped.

Soon, some poor middle-aged businessman sitting in the row ahead of Munson tried some simple, polite reason.

“Could you please lower that?” the man said.

“Mind your own business, f—face,” Munson shot back. The music stayed loud.

Munson wasn’t an angel. But he was authentic.

***

As of Aug. 2, 1979, Munson had logged 516 hours of flying time, 33 in a Citation. On that day, he was proudly showing off the interior of his new jet — customized in Yankee blue, of course. He talked two men — David Hall, his former flight instructor, and Jerry Anderson, a Canton friend — into joining him in the plane, and at 3:41, N15NY took off into the sky over Canton. The New York Daily News ran a comprehensive summary of Munson’s final minutes in 2004, but here’s how the crash happened.

Munson ascended to 2,800 feet, then made a sweeping lefthand turn and came back in for a touchdown landing. He took off again, and made another touch-and-go landing, and then another.

On the final approach, matters took a turn. Per the tower’s instructions, Munson had gone right rather than left, a tougher move for an inexperienced pilot. On the descent, he drifted off the proper glide slope, the guideline for how to land safely. For whatever reason — inexperience, overconfidence, ignorance — he waited too long to deploy the landing gear, and then, once the gear was down and dragging on the plane, Munson failed to drop the flaps to give the plane more lift.

"The added drag of the gear, the reduced power and the reduced lift available without flaps extended placed the aircraft in a dangerous situation," an NTSB report would later say. Munson failed "to recognize the need for, and to take action to maintain, sufficient air speed to prevent a stall during an attempted landing.”

The plane kept descending, tearing off treetops and losing a wing. It dug into the ground 870 feet from the edge of the runway, skidded across a field, slammed into a tree stump, and finally slowed to a stop on Greensburg Road near the runway.

“Thurman flew that airplane to the last nanosecond,” Anderson told the Daily News. "He kept it under control and brought us down. He never panicked. He saved our lives."

In depositions, Hall indicated that in his final moments, Munson asked if his two passengers were all right. Noticing smoke and flames rising, he said, “Fire extinguisher,” and then, finally, “Help me, Dave.” But Munson was pinned in the wreckage, with fire ravaging the plane.

Hall and Anderson were not able to free Munson. A coroner’s report would later indicate that Munson had broken his neck and was paralyzed. The cause of death was listed as smoke inhalation. (Munson’s wife Diana has said on multiple occasions that she does not blame Hall and Anderson for leaving the plane; the flames were too intense to survive.)

Steinbrenner was one of the first to get the call, and he summoned the team’s front office staff. There, in one of the darkest moments in Yankee history, Steinbrenner showed why he’d turned the Yankees into a worldwide juggernaut, according to those in the room.

He began by dispatching staffers Larry Wahl and Gerry Murphy to Canton to work with Munson’s family and local police. Then, without a pause and without a break, he turned to his baseball operations people and began assessing how the team would replace Munson on the field.

“The guy, love him or hate him, he was brilliant,” said Wahl, at that point a public-relations assistant in the Yankees’ front office. “He knew what he wanted to do, and he was on top and in charge in every way … He had every aspect of what was going on under control, and he knew what he wanted to do. It was George in one of his finest moments.”

The time Steinbrenner got the best of Thurman

Steinbrenner and Munson had always enjoyed a close, if not always positive, relationship. Steinbrenner had famously promised that Munson would always be the highest-paid Yankee on the team, then tried to disguise the fact the newly-arrived Jackson would be making more.

One of Steinbrenner’s best-known mandates was his ban on facial hair outside of mustaches, a decree that began in 1973 when he spotted Munson, among others, unshaven with long hair curling out beneath his cap. Munson rebelled against the decree — Munson rebelled against any decree — by showing up to a preseason exhibition game against Syracuse sporting a thatchy growth of beard.

Steinbrenner knew that thundering against Munson would do no good. He also knew how close Munson and Billy Martin were. So, as Klein recalled it, Steinbrenner played a little chess.

“I’m not going to fault Munson for having the beard,” Steinbrenner said. “The manager is the one who’s supposed to enforce the rules. So it shows the manager doesn’t have control. If he keeps the beard going, it’s going to be bad for Billy Martin.”

The beard vanished shortly thereafter.

***

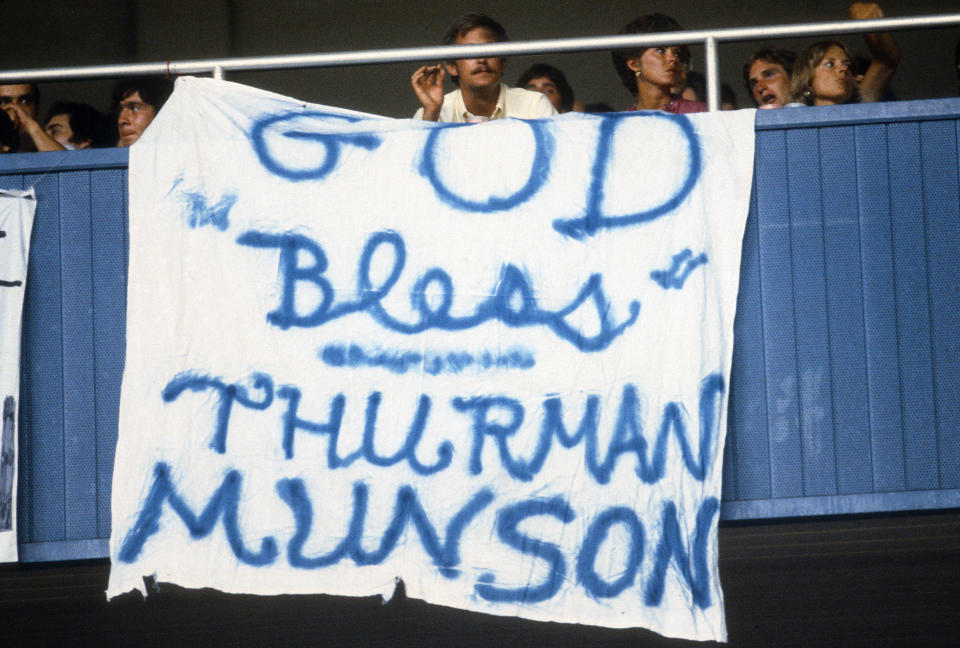

The news filtered its way out across the wires, taking hours to reach the entire roster. Reggie Jackson heard it on the radio while driving his Rolls-Royce in Connecticut. Bucky Dent learned from a parking-lot attendant, and nearly crumpled to the ground in grief. Steinbrenner managed to reach Hunter, Piniella and Graig Nettles. Gossage was preparing to go to a Waylon Jennings concert when he got the call. Roy White didn’t learn until a newspaper reporter called asking for comment.

“That’s somebody I thought I was going to be friends with the rest of my life,” Nettles would say later, and he wasn’t alone.

Munson died on a Thursday. The Yankees had a four-game series against the Orioles, and sleepwalked through the first two, losing both. Somehow, the team managed a win on Sunday afternoon, and early Monday morning, the entire team boarded a charter plane for Canton for Munson’s funeral.

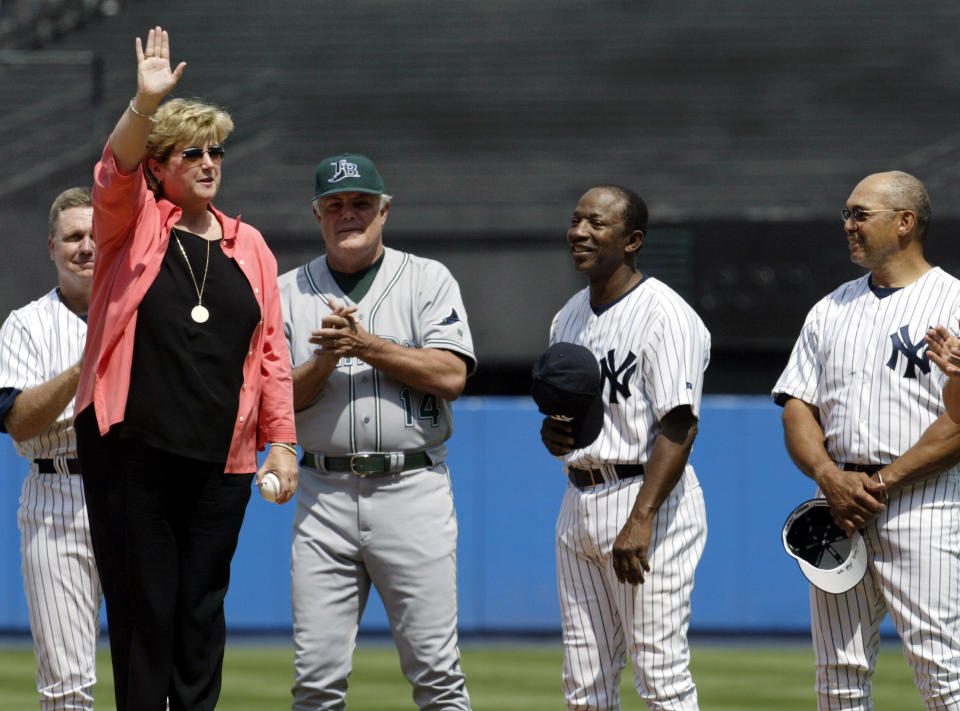

Thousands of grieving fans and friends entered the Canton Civic Center for Munson’s service. Piniella and Bobby Murcer, two of Munson’s dearest friends, spoke words they couldn’t have imagined they’d be saying just three days earlier.

"Thurman Munson wore the pinstripes as No. 15,” Murcer said. “But in living, loving and legend, history will forever remember my friend as No. 1."

The time Murcer honored Thurman the finest way possible

One more story. It seems impossible to fathom, but the Yankees went ahead with a nationally televised night game against the Orioles on Monday, Aug. 6, the day of Munson’s funeral. Steinbrenner considered cancelling the game, but Diana Munson talked him out of it.

As fans arrived at the ballpark, a message on the Yankee Stadium scoreboard read, "Our captain and leader has not left us today, tomorrow, this year, next ... our endeavors will reflect our love and admiration for him."

Murcer, just hours from delivering a eulogy to his friend and going on 30 hours without sleep, worked to convince Martin to put him in the starting lineup.

"Billy, I'm not tired,” Murcer said. “For some reason or another, I feel like I need to play in this game. I wish you would play me.”

“Are you sure?” Martin said.

“Yes,” Murcer repeated, “I’m sure.”

As the Yankees took the field to start the game, catcher Brad Gulden left the spot behind home plate vacant in Munson’s honor. The Orioles, at that time one of the AL’s best teams, rode home runs to a four-run lead.

But in the bottom of the seventh, Murcer — Munson’s longtime friend and the last player to see the Yankee captain alive — blasted a Dennis Martinez pitch into the right-field bleachers to cut the Baltimore lead to 4-3. Two innings later, again at the plate with two men on, Murcer lashed a two-strike single to left field to win one of the most dramatic, and painful, games in Yankee history.

***

The Yankees kept Munson’s locker preserved exactly as it had been on Aug. 2 for the rest of that season, shin guards, glove, orange chest protector and all. But as the days wore on, the tribute’s meaning shifted from honorary to oppressive.

“Nobody was going to use it,” Klein said. “It was a centrally located locker, right near the entrance to the trainers’ room. Even after several weeks had gone by, it was like a little odd to have the locker there. Nobody would have forgotten him.”

“I don’t know if it was a good idea to keep the locker fully stuffed with his things, with his name up there,” Appel agreed. “It was so haunting. There was no place to go to just [have] a regular clubhouse, to play cards with your teammates.”

Murcer’s game-winner would be one of the final highlights of a dismal season. The team deployed Gulden and Jerry Narron at home plate, but neither came close to matching Munson’s impact, and no one truly expected that.

The Yankees had been 14 games out of first place at the time of Munson’s death, and they finished the year almost that far back, in fourth place in the AL East. They wouldn’t win another World Series title until 1996, long after anyone who’d shared a locker room with Munson had moved on and retired.

“After awhile, it went from being sad and somber, to OK, to being able to joke about ‘what would Thurman have thought of this?’” Klein said. “No way he was ever going to be forgotten. Even several seasons after he was no longer there, he was really a presence on the team.”

Munson’s locker, later preserved behind plastic, remained in the home locker room at old Yankee Stadium for as long as The House That Ruth Built stood. More than a decade after Munson’s death, Derek Jeter, the team’s first captain since Munson, took up residence in the locker next to Munson’s shrine. When the team moved to its new stadium, Munson’s locker came along. It’s now on display in the stadium’s museum.

Munson’s name lives on in New York sports lore. AHRC NYC, an organization dedicated to helping children and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities, has held 39 Thurman Munson Awards dinners honoring New York athletes and business leaders. This year’s honorees included the Yankees’ Didi Gregorious and Miguel Andujar. Diana Munson is there to present a keynote address, every year.

In the days after his death, Yankees fans and media advocates began a push for Munson to get immediate induction into the Hall of Fame. Their precedent, they argued, was Roberto Clemente, who’d entered the Hall eight years before after his own tragic death in a plane crash.

But emotion alone wasn’t enough to sway the minds of Cooperstown voters. Munson’s value to the team was immeasurable — as in, literally unable to be measured. How do you quantify heart, desire, willpower? Where’s the statistical category for Got Your Back?

Munson’s numbers, on the other hand, put him in the category of good-but-not-great catchers like Tim McCarver, Terry Steinbach and Sandy Alomar — names you might know, but more from baseball cards than award plaques. Stripped of context, his slash line of .292/.346/.410 and his career WAR of 46.1 aren’t particularly remarkable. Munson got 15.5 percent of the vote in his first year of eligibility, then never topped 10 percent after that. He dropped off the ballot after 15 years, in 1995.

Still, Yankee fans don’t need Cooperstown’s validation. They know what they had when Munson was around, and they know what they lost when he died. Munson’s No. 15 holds down one corner of the large left-centerfield sign listing all the team’s retired numbers, just to the right of Whitey Ford’s No. 16 and just above Mariano Rivera’s No. 42. Even as the memories start to fade, the name and the number — and the shock — never do.

“This was the captain of the defending world champions, on an off day,” Appel said. “Stories like this don’t happen, not before and not since. A player of that magnitude gone, just instantaneously.”

____

Jay Busbee is a writer for Yahoo Sports. Contact him at jay.busbee@yahoo.com or find him on Twitter or on Facebook.

More from Yahoo Sports: