'Making us sick inside': Gas project will destroy sacred site, Indigenous elders fear

This is the second story in a four-part series, reporting on the community impact of the controversial Narrabri gas project. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following article may contain images of deceased persons.

Australia is on track to destroy an Indigenous nation’s sacred cultural asset, if a controversial coal seam gas project goes ahead, community leaders warn.

Members of the Gomeroi nation say energy company Santos’s gas drilling at Narrabri, in northwest NSW, poses an unacceptable risk to the country’s largest underground water source, the Great Artesian Basin.

Fearing toxic elements and salts dredged up in the extraction process could poison her people’s water, native title applicant Polly Cutmore has been vocal in her opposition to the plan.

“Our artesian is not up for sale and neither are we,” Ms Cutmore told Yahoo News Australia.

“We don’t know what this mob is up to, we don’t trust them.

“It’s colonialism coming back again.”

Ms Cutmore said she feels a responsibility not just to her own community, but also to the parched towns downstream which receive water through the region’s complex river system.

“That means we’re going to be poisoning our own people,” Ms Cutmore said.

“We can’t have that, that’s our family down the river.

“We can’t poison them… we can’t be greedy people up this way, we’d get in trouble doing that sort of stuff.”

Mine opponents vow to keep fighting project

Ms Cutmore is supported by her sister Toni Wright and traditional owner Sheryl Nichols who have come to meet at the Pilliga Bore Baths.

Despite the gas project being 80km northwest from the project site, the water is connected by deep underground water courses.

At the Pilliga bore, water flows to the surface at 37 degrees Celsius, attracting a trickle of grey nomads who park their caravans and soak their weary limbs.

The location remains an important meeting place for Gomeroi people, and the surrounding paddocks contain scar trees which were once used to make coolamons for carrying newborn babies.

Water is women’s business, and Ms Nichols says protecting country is causing stress to her and other women in the community.

“It’s also ruining our hearts, it’s making us sick inside,” Ms Nichols said.

“We can’t let them keep doing it.”

Compromising water ‘doesn’t make any sense’

Knowledge of the water system has been handed down by elders for generations, these teachings grow over an individual’s lifetime into practical skills and a deeper understanding of country.

They have survived on this hot, dry landscape for thousands of years by knowing how to access fresh water.

Despite shopping centres, houses and roads being built on top of cultural sites, the link Gomeroi people maintain with country has not wavered.

Cultural practitioner Steven Booby explains that the Namoi river is literally referred to as a breast in Gamilaraay language, as it sustains those living in and around it.

Country, he says, functions the same as a body does, with many of the springs around the Pilliga referred to as hearts.

“If we look at the circulatory system within the body, and if you put poison into your heart, then that’s going to ultimately spread to everything,” he said.

“The ideology that we could look at doing something so signifiant that literally attacks ‘the hearts of country’ without even guaranteeing (the project’s) safety, then why is that even being considered?

“People say common sense will prevail. Well, common sense is not that common really, is it?”

When Mr Booby was a child, his grandfather used a “cryptic approach” to learning culture, asking him what the most important thing is on earth is.

“He’d never give you the answer, you’d have to figure it out,” Mr Booby said.

“His questioning and his guidance was always built around you and your own journey and your own track.

“He’d say to me ‘Boy, what’s the most important thing?’”.

Firstly, the young Mr Booby answered “family”, and his grandfather nodded and moved on. Months later the question came again.

This time he answered “food”, then “respect”. He hadn’t found the answer yet, and the conversation in total lasted for two years.

The fourth time his grandfather asked the question he answered “water”.

“Now you’re talking,” his grandfather replied.

Project wouldn’t go ahead at Bondi, says local

Despite local opposition to the project, decisions allowing it to proceed have been made by government in Sydney, leading Mr Booby to ponder whether locals should “Brexit” from the capital.

He argues that releasing waste water from coal seam gas extraction would not be tolerated in Sydney’s waterside suburbs like Cronulla or Bondi.

“What do you think would happen if I dumped it in Manly Beach, Coogee Beach, the Shire?” he said.

“It would probably kill everything. They wouldn’t do it there, why are they doing it here? What’s the difference?”

Sitting on the banks of the Namoi River in Narrabri, Mr Booby scoffs at the idea that regional towns like his suddenly need “saving” when they have been continuously occupied by the Gomeroi for generations.

What he fears is that towns which rely on underground water for survival, especially during drought, would become uninhabitable if clean water supply is compromised.

“What happens when all of this is dead, do we pick up Narrabri and move it 100km east?” he said.

“Do we pick up Wee Waa, do we pick up Walgett, do we pick up Coonamble, Pilliga, Burren Junction, Brewarrina, all these places that are on the same river course?”

“Do we relocate them because there is no clean, fresh, drinking water, or do we truck it in?”

For many in Mr Booby’s community, the memory of being forced into a reliance on government rations is still fresh.

Water flows free for now, and the fear of losing access and being forced into dependency is real.

Mr Booby is urging all Australians to pause and listen to local Indigenous people about the country, before it is drilled for gas.

He notes it wasn’t until the Black Summer bushfires were over that interest in cultural burns grew, so he is urging all Australians to start “acting now” and learn about the Pilliga and its water.

“We see a lot of people calling themselves Australian… but what does that actually infer, what does that actually mean?” he said.

“You want to call yourself Australian but you don’t want to learn about the country or the water system, or what’s valuable here, or what needs to be looked after and preserved.

“Then you call yourself Australian, or are you just hanging onto some eighteenth century colonial ideology?

“Being born here yourself you are now part of this.”

‘They’re selling all our stuff to China’ say Indigenous leaders

Accessible parts of the Pilliga State Forest are now no-go zones. Anti-coal seam gas campaigners Pilliga Push have photographed NSW Forestry Corporation signs restricting access to areas where Santos is operating.

Locked gates accompanied by a warning that trespassers will be prosecuted now block some road access inside the park.

Gomeroi woman Ms Nichols says access to land for the continuation of cultural practices is becoming increasingly difficult.

Leasing her people’s land to the mining industry is just another step in the process of colonialism which has seen Indigenous people’s property stolen and sold off, with little benefit to the traditional owners.

“Why should they come in and destroy our Pilliga scrub with our wildlife and everything else in there?” Ms Nichols said.

“With our wildlife and everything else in there, beautiful trees, beautiful flora and fauna.

“All they can see in their eyes is dollar signs and destruction.”

While Santos is an Australian based company, if the gas pipelines are eventually linked to ports, many locals believe gas extracted from the region could be exported to international markets.

Ms Nichols argues minerals and gases under the earth are part of the cultural landscape and should not be sold off overseas.

She notes a wider “problem” of Australian assets being sold off overseas, and points across the way to areas of land sold to foreign owned companies.

“They’re selling all our stuff to China, all the big overseas companies, it’s ridiculous,” she said.

“Pretty soon it’s not going to be called Australia, it’s going to be China Two.”

Gomeroi man urges his people to negotiate with Santos

While most Gomeroi people who spoke to Yahoo News Australia said they are opposed to the project, some native title claimants have advocated for Santos’ coal seam gas drilling to go ahead.

One Indigenous man, we’ll call John Smith, who spoke to Yahoo News Australia on the condition of anonymity said the “world has changed” and that money is critical to improving living standards for Aboriginal people.

Proud of securing jobs for Gomeroi people through negotiations with the resource industry, Mr Smith argues work will create advantage for families and help break the cycle of “poverty and despair” that affects many in the community.

With statistics on Indigenous wellbeing going backwards, Mr Smith says the government cannot be relied on to create change. In his eyes they have failed his people.

He would like to see continued discussions over resources like gas, but says royalties currently paid to Indigenous people by mining companies are a “pittance”.

“We don’t want to take freehold land, but what we want to have happen is proper compensation for the taking of our country,” he said.

“Try and remunerate that. We’re talking billions of dollars, not what’s currently being offered.

“Even if we accumulate more agreements with other mining companies, it’s just not going to be enough to deal with the oppression, and the marginalisation that we’ve experienced as a result.”

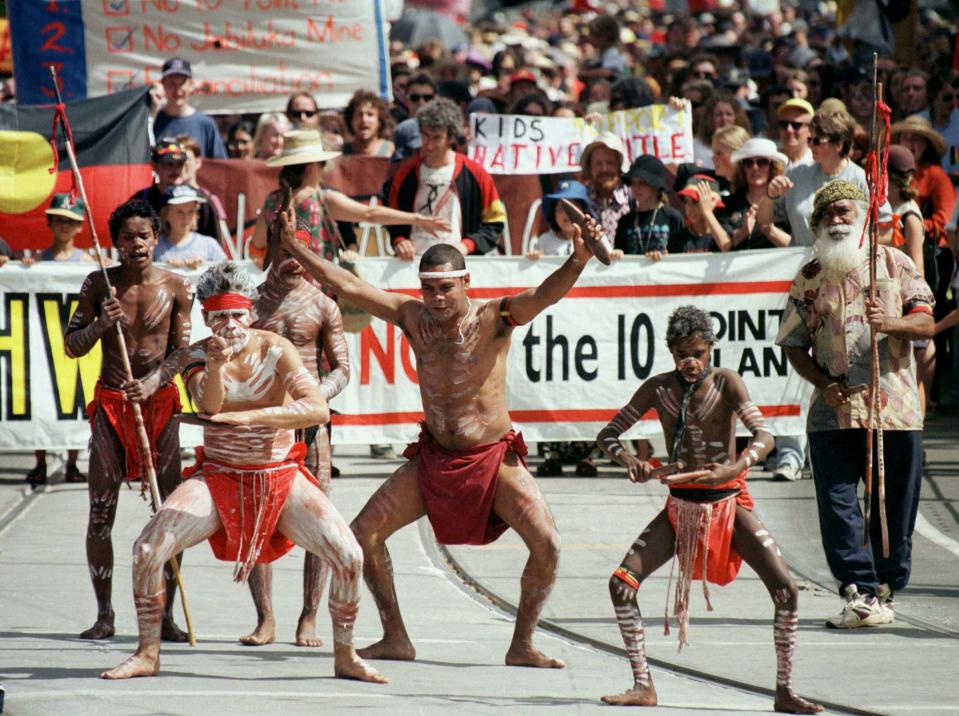

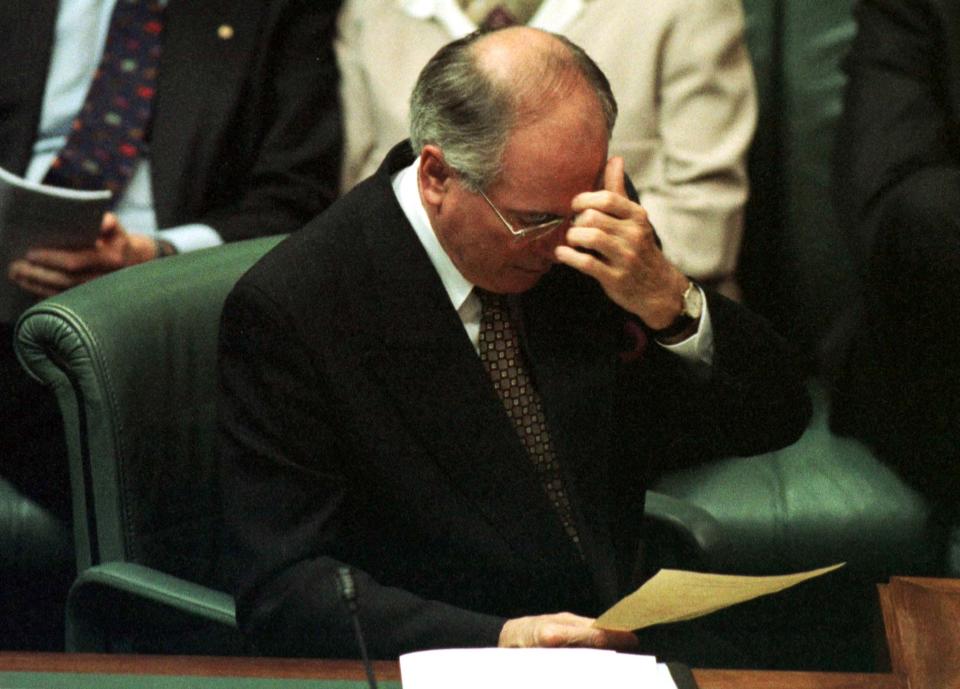

Native title rights eroded during Howard years

While native title was supposed to improve the lives of Aboriginal people across Australia, changes under former prime minister John Howard have affected their ability to benefit from their country, according to Mr Smith.

He says the Native Title Amendment Act 1998 has put Aboriginal people in a position where they have to negotiate, but receive minimal benefits.

“You win the high courts in a legal precedent with the sword, and then you’re put to the pen,” he said.

“If native title rights exist over resources in our country that means we should be able to benefit in a more productive manner.

“Back in the 1960s and 1970s our people were protesting specifically for those resource rights, but where are the benefits from our country?

“They just don’t exist.”

‘Our people are still living in poverty and despair’

Mr Smith is concerned if his community refuse to negotiate with resource companies in the area they will lose out.

If the Gomeroi people will not agree to an Indigenous Land Use Agreement with Santos, he fears the company could go to arbitration and this he worries would affect renumeration.

“When you take it to the court of arbitration Aboriginal people lose,” he said.

“Culturally and spiritually people don’t want to accept these agreements.

“Our people are still living in poverty and despair, what do we do?

“Here we are sitting on the new coal frontier, there’s gas galore and we get crumbs off the table, and they want to do it in our spiritual places.”

Santos working with Gomeroi people, it says

Santos declined to be interviewed by Yahoo News Australia and did not respond directly to questions requesting information about negotiations with native title applicants, but provided written statements.

“Santos is working constructively with the Gomeroi native title applicants on an Indigenous Use Land Agreement,” a Santos spokesperson wrote.

“Santos will continue to work constructively with the Gomeroi native title applicants with a view to reaching agreement.”

The company say they guarantee water from the site will not leak into water systems, and said they will protect Indigenous sites.

“Protection of Indigenous cultural heritage is required as part of the project conditions of consent and it is a commitment of Santos, regardless of compliance requirements,” Santos wrote.

Local MP says Indigenous community not given a voice

The NSW Independent Planning Commission approved Santos’ proposal in October, after the plan was stalled for almost a decade.

The NSW government has thrown their support behind the project, and the Commonwealth, which is touting a gas-led recovery to secure Australia’s financial future after the pandemic, is expected to do the same.

Amid the gas debate, Shooters Fishers Farmers MP Roy Butler ended 69 years of National Party rule, winning the Seat of Barwon in 2019.

In January he said the risk from the gas project may be small, but the consequences if anything goes wrong are enormous.

“We can’t put the Genie back in the bottle if we compromise groundwater,” he said.

Part 1: Farmers fear 'there will be blood spilt' as coal seam gas battle heats up

Part 2: Gas project will destroy sacred site, Indigenous elders fear

Part 4: Concern for wildlife after contentious plan approved

Mr Butler argues that the wider Gomeroi community, as well as other Indigenous nations downstream have “not been given a voice in this”.

“Aboriginal people who rely on bore water at Coonamble, Walgett, Bourke, all of those places, have an interest in this too and they should have a say in it,” he told Yahoo News Australia.

“We’ve got gas and oil people planning the recovery from the pandemic, it’s a bizarre situation.”

While the Narrabri gas project has been touted as a way to ensure NSW has gas supply into the future, Mr Butler says the state has amble supply and that the resource is being mismanaged.

“If the federal government put Australians first then we wouldn’t have this problem,” he said.

“Australia exports around 3000 petajoules a year, mainly to Asian markets.

“The Narrabri project is for just 70 petajoules, so a different domestic gas reservation policy, or a public interest test on exports would mean that the project at Narrabri is just totally not needed and we would be able to drive lower energy prices.”

Time for peace say local elders

Rather than drilling into Gomeroi land for coal seam gas, Ms Cutmore is now encouraging Santos and their investors to come and learn from her people.

The community have practices that go back thousands of years and have enabled them to survive off the land without gas or mining.

As Ms Cutmore remains firm in belief that the project will not go ahead, she said she wants to remind Santos that the Pilliga has never been ceded and that a clean environment is more important than any renumeration.

“We don’t want their money,” she said.

“We just want clean air, want to be able to sit around with our families, enjoy food, have a good laugh, have a little argument, come back and sit down and have another feed.

“We want to live together in peace, don’t you?

“I think it’s about time peace came to this country.”

Do you have a story tip? Email: newsroomau@yahoonews.com.

You can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter and download the Yahoo News app from the App Store or Google Play.