From ruins to renaissance: How the sports card market became appealing to investors

As Clayton Kershaw fought his way out of a third-inning jam in Game 5 of the World Series last Sunday night, a Connecticut man nervously squirmed on his living room sofa like his own legacy was at stake.

Michael Pruser isn’t a Los Angeles Dodgers fan, nor did he place a bet on the game. He watched with clammy palms and a pounding heart because every pitch had the potential to influence the value of Kershaw’s baseball cards.

Of the $1.6 million that Pruser has poured into the booming sports card market, Kershaw is one of his biggest investments. Pruser has spent $40,000 to control the market for Kershaw’s most prized rookie cards.

Entering the World Series, Pruser valued his Kershaw collection at $150,000. He estimated that could rise to $250,000 if Kershaw shed the reputation of postseason underachiever and led the Dodgers to their first title in 32 years. That made for some tense moments for Pruser as he sat through Kershaw’s Game 5 tightrope walk.

“It was torture,” Pruser said. “I don’t know why I do it to myself. When you have so much money invested in a guy and you watch him pitch for three hours, you sweat. It’s a strange feeling. It’s almost like you’re on the mound yourself.”

Hard as it may be for traditionalists to believe, Pruser is far from the only sports card enthusiast whose investment portfolio mostly consists of colorful pieces of cardboard. In an effort to capitalize on an unexpected upsurge in the sports card market, an increasing number of high-rolling investors are trusting their money to LeBron James and Patrick Mahomes instead of Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan.

In other words, they are eschewing investing in stocks or real estate and plunging gargantuan sums into coveted football, basketball and baseball cards.

Those who prefer sports cards often point out that tracking their investments is more fun. Try cracking open a beer, turning on CNBC and spending three hours cheering whenever green numbers flash across the stock ticker.

More importantly, if investors are smart with their money, sports cards can be more profitable. After two decades of decline, contemporary card sales have recovered over the past five years and accelerated anew amid the pandemic, smashing all-time records at a time when much of the American economy is sputtering.

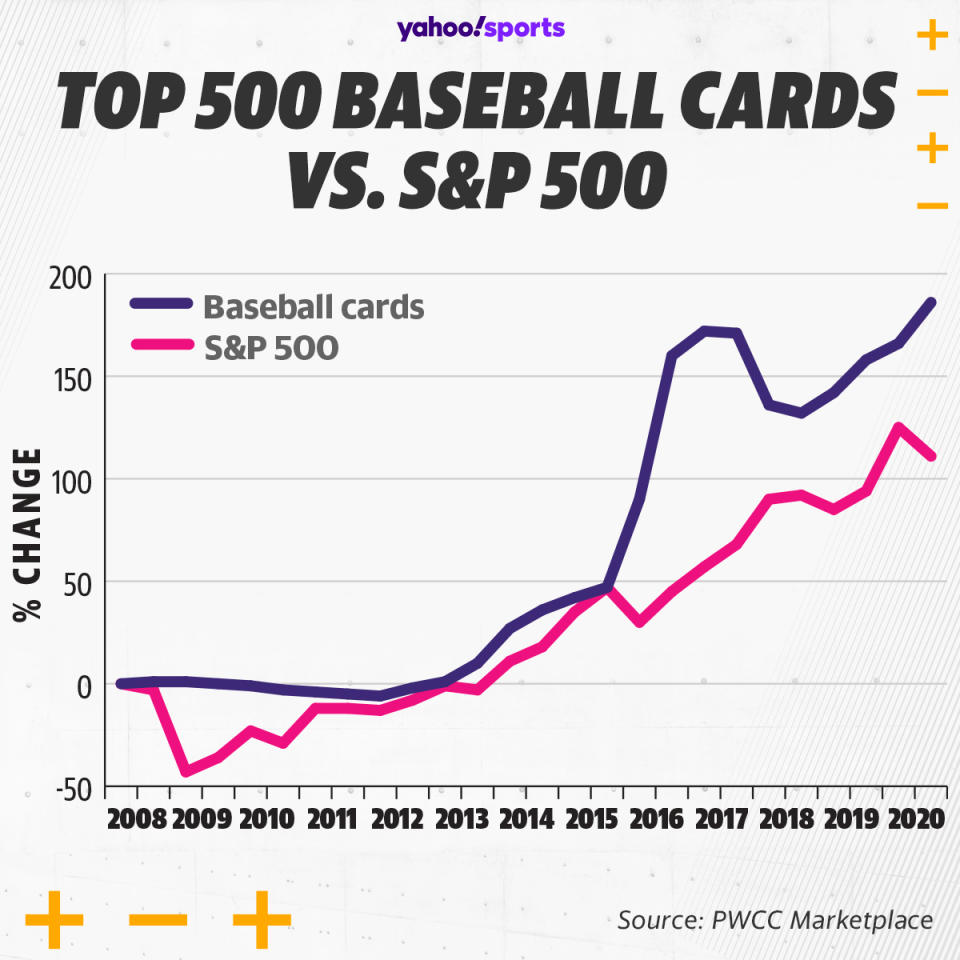

A major auction house recently compared the performance of blue chip stocks and the high end of the sports card market. PWCC Marketplace’s index of the top-performing 500 cards printed before the year 2000 produced a return on investment of 216 percent since 2008. By contrast, the S&P 500 delivered 135 percent during that same timespan.

It’s not just older cards that command big money anymore either. In fact, this year the prices of modern cards have dwarfed the vintage market. A one-of-a-kind autographed Mike Trout rookie card sold at auction in August for $3.93 million, the highest price a single card has ever fetched. Autographed limited-edition Giannis Antetokounmpo and LeBron James cards also sold for more than $1.8 million apiece at separate auctions earlier this year.

“The sports card market is the best spot to put your money,” said Jared Bleznick, a professional poker player and sports card collector who co-owns Blez Sports Cards.

“It’s very hard to make a lot of money day trading. It’s very hard to make a lot of money in real estate. It’s very hard to make a lot of money playing DFS or gambling on sports. You have to be smart with how you invest in the sports card market, but it’s probably easier to make a decent return there than almost anywhere else.”

The evolution of the sports card market

How did sports cards evolve from playthings to commodities? The story begins more than 40 years ago when nostalgic Baby Boomers began reacquiring their favorite baseball cards from their youth.

Since so many of those old cards had been tacked to walls, placed in bicycle spokes or lost to flooded basements, the resulting scarcity created a lucrative market for stars of a bygone era. Buyers shelled out hundreds or even thousands of dollars for cards featuring the likes of Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle or Willie Mays.

By the late 1980s, those prices caught the attention of everyone from kids, to collectors, to speculators. Hoping new cards would appreciate in value the same way the older ones did, they snapped them up as soon as they hit the shelves and squirreled them away in plastic cases.

At the height of the sports card craze, almost every suburban strip mall seemed to have a hobby shop. Manufacturers ramped up production to meet demand and flooded the market with millions more cards than were printed in previous eras. Major League Baseball also contributed to the deluge by licensing a flurry of new manufacturers.

It was an era of prosperity for the sports card industry. Then the bubble burst.

The sports card market cratered in the mid-1990s when customers recognized that any cards printed in the previous 5-10 years were overproduced and largely worthless. In 1991, sports card sales were a $1.2 billion industry. Twenty years later, it was less than a fifth of that.

Avid collector Joe Davis opened a suburban Atlanta sports card shop in 1991 the same week he graduated college. He says stubbornness and prayer were the only reasons he didn't go out of business over the next two decades like so many other hobby shops did.

“We were on the verge of bankruptcy multiple times,” Davis said. “There were times when a product would come out and we were happy to sell it for anywhere close to what we paid for it. There was no worry about the profit margin. The focus was, ‘How little can we lose on it?’”

The sports card revival

The first step toward an eventual industry-wide recovery was the surviving manufacturers learning from their mistakes and reinventing themselves. One by one, they limited production and marked cards with serial numbers to show collectors how many were printed.

By the 2000s, card makers also learned to offer new products with an eye toward collectors. They began to include in packs an assortment of rare, sometimes one-of-a-kind lottery-ticket-type cards featuring autographs, bat splinters and swatches of game-worn jerseys.

That restored scarcity and the thrill of the hunt to the sports card market, as did the emergence of Professional Sports Authenticator (PSA) and other third-party grading firms. Card owners can now hire a PSA expert to painstakingly assess a card’s condition with a jeweler’s eye for imperfections.

A perfect grade of Gem Mint 10 is unusual even for a freshly opened card and can dramatically increase the resale value of an older card — even one from the junk-wax era. A PSA-10-graded version of Ken Griffey Jr.’s iconic 1989 Upper Deck rookie card now routinely sells on eBay for about $1,500, roughly 20 times what it would have fetched 25 years ago.

With cards becoming an investment commodity again and the U.S. economy recovering from the 2008 recession, the sports card market enjoyed a renaissance the past few years.

Then COVID-19 arrived, sports paused and the resurgence ... accelerated.

Many sports gamblers who couldn’t bet on games or leave their homes turned to flipping sports cards to fill that void. Daily fantasy sports enthusiasts did the same. Middle-aged parents who hadn’t bought sports cards since the early 1990s introduced their childhood hobby to their kids and returned to it themselves, this time with considerably more disposable income to invest.

The byproduct has been a record-setting year for Davis and other sports card shop owners. Davis can’t order enough cases of the most popular sports cards to satisfy the torrent of new customers that peruse his spacious new 10,000-square-foot shop or his thriving eBay store.

“There are some products that I can only get two cases of and I could sell 50 without even trying,” Davis said.

“We’re very thankful for the health of the industry. I came close to throwing in the towel a few times, but I believed in what we were doing and I believed the hobby would turn around. Thankfully I held on.”

It’s clear the sports card market is in the midst of a second period of prosperity. The challenge for investors has been figuring out how best to capitalize.

Forecasting the market

In 2018, a notoriously brash, loud-mouthed sports gambler made a bold purchase and an even bolder prediction.

After buying a one-of-a-kind autographed Mike Trout rookie card for $400,000, he pledged not to sell for anything less than $3 million.

“Everyone laughed at me,” said Dave Oancea, better known in gambling circles as “Vegas Dave.” “They didn’t know I had a vision.”

No one’s laughing anymore now that the surging sports card market has enabled Oancea’s promise to come true. Oancea sold the Trout card to an undisclosed auction bidder in August for a record-setting price of $3.93 million, surpassing the $3.12 million a buyer paid in 2016 for a Honus Wagner tobacco card once owned by Wayne Gretzky.

The value of Trout’s 2009 Bowman Chrome Superfractor card stems from the fact that it was the only one the card maker ever printed. It became the sports card equivalent of a Wonka ticket as Trout evolved from a late first-round pick, to a can’t-miss prospect, to the sport’s top all-around player.

In addition to the Superfractor, Oancea forked over hundreds of thousands of dollars to buy one of the five existing Trout red refractor cards and eight of 25 Trout orange refractor cards ever produced. He paid more than market value on some of those in an effort to control the market for Trout’s most coveted limited-edition rookie cards.

“The cards would be valued at $50,000 and I would offer $150,000 to get it out of their hands,” Oancea said. “They thought they were ripping me off and getting a great deal, but I wanted a monopoly.”

Most sports card investors can’t afford to buy cards that cost as much as houses like Oancea apparently can, but they can still learn from the multimillion-dollar profits his approach netted. It’s a reminder that the combination of a celebrated player and a prized card can produce a staggering profit, especially in a booming market like this one.

Retired icons are often the most stable longterm investment, but there’s seldom enough demand for their cards to rapidly ascend in value. Top prospects have the most upside, but the risk is far more bust than boom. The sweet spot in the risk-reward scale are today’s superstars, especially players with a massive following, Hall of Fame potential and the bulk of their career left to add to their litany of accomplishments.

Mark Demers, an assistant manager at a Massachusetts bank, received a recommendation from another investor earlier this year to seek out Giannis Antetokounmpo cards. Not only was the 25-year-old Antetokounmpo in the midst of a second straight MVP season, he also had the Bucks in position to contend for their first championship since 1971.

At first, Demers plunked down $15,000 on one of only 75 known PSA-10 versions of Antetokounmpo’s Prizms Silver rookie card. A month later, he snapped up a second of those same cards for $16,500. Then he unexpectedly met a collector selling the even more scarce Prizms Orange version of that card, and he reluctantly forked over $32,000 for that one.

“Now I’m up to $64,000 into three Giannis cards,” Demers said. “That’s a lot of money. I’m not a rich person. I work a 9-to-5 job. But I was always taught, if you don’t want to lose money, invest in the blue chips.”

Though Antetokounmpo’s Bucks ultimately crashed out of the playoffs in the second round, Demers shrewdly sold before that happened. He said he netted a total of $147,000 from the sale of three cards this summer, more than double what he spent on them just a few months earlier.

“That’s how hot the market was going into the playoffs,” Demers said.

While investing in former MVPs like Trout and Antetokounmpo provides longterm value and consistency, the blue-chip stocks of the sports card market aren’t the only path to a payday. Investors can also win big by putting money into penny stocks. The trick is figuring out which undervalued prospect is poised to make a leap.

Gambling on futures

Chris Steuber is a former NFL draft analyst and Arena Football League director of player personnel, but the lifelong sports card enthusiast now uses his scouting credentials for a slightly different purpose.

He studies the film, background and performance of top college prospects to determine whose rookie cards will be the best investments.

“I think my eye for talent has always helped me in the trading card business,” Steuber said. “A lot of people go for prospects on their favorite team. I do my own investigative work and try to watch as much film on these players as I possibly can. I’m certainly not always right, but I believe I have more hits than misses.”

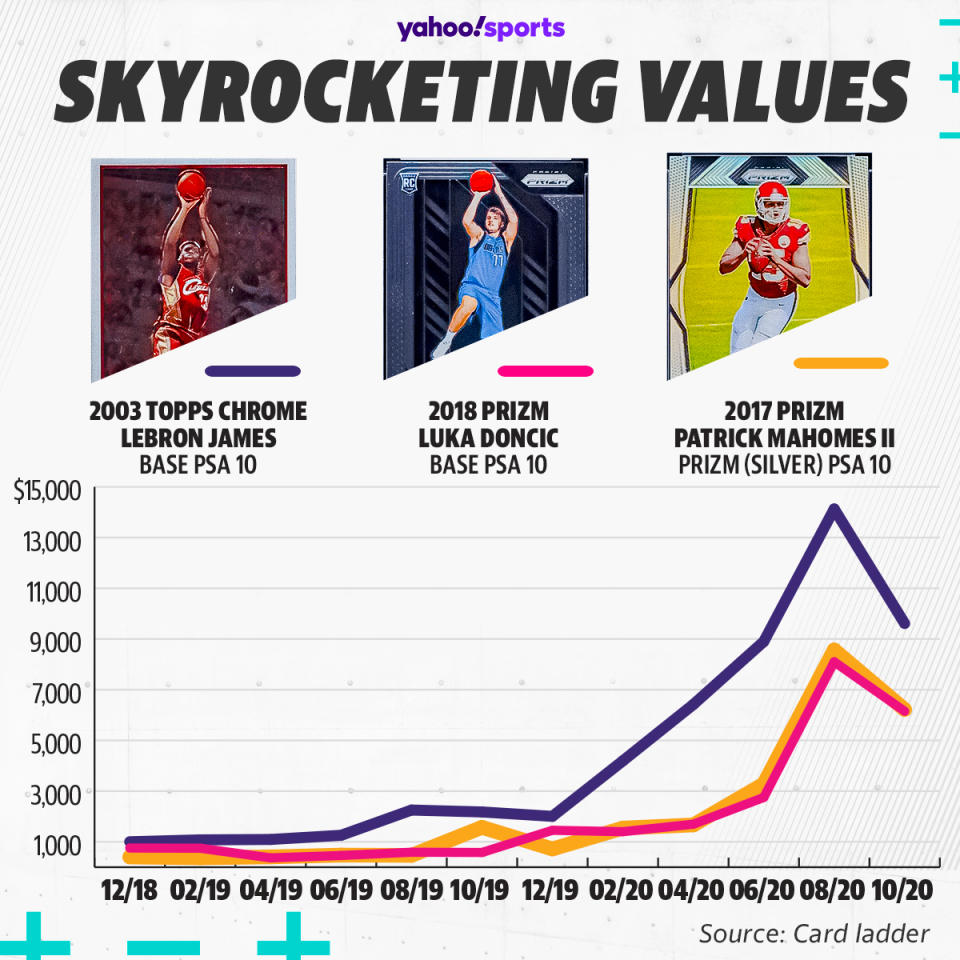

Steuber’s most profitable hit was identifying Patrick Mahomes as the best quarterback in the 2017 draft class. Others were touting fellow 2017 first-round picks Deshaun Watson or Mitchell Trubisky, but Steuber liked Mahomes’ arm talent, pedigree and mental makeup, as well as the fact that he would learn from Alex Smith for a year and play in Andy Reid’s quarterback-friendly system.

If I was a GM in #NFL & was told by my owner to draft a QB in this year's draft, the guy I'm targeting is @PatrickMahomes5. Big-time future!

— Chris Steuber (@ChrisSteuber) March 4, 2017

Before Mahomes’ rookie season began, Steuber purchased 25 of his Prizm rookie cards at roughly $15-20 apiece. Raw versions of the card now routinely sell for $500. PSA-10 cards fetch much more than that.

“I just knew the kid was legit,” Steuber said. “If you invest in the right cards and the right players, you are going to make money.”

If only it was always that easy.

When Pruser started investing in sports cards eight years ago, a quartet of highly touted baseball prospects were among his top targets. He invested between $20,000 and $75,000 apiece on Mike Zunino, Tony Cingrani, Oscar Taveras and Jose Fernandez.

Zunino and Cingrani didn’t meet expectations. Taveras and Fernandez tragically died. Taveras, a promising St. Louis Cardinals outfielder, perished in a 2014 car accident and Fernandez, the live-armed Florida Marlins ace, died in a 2016 boating crash.

“I obviously felt most sorry for the family and friends, but I also lost a small fortune,” Pruser said. "From that point on, I decided to focus only on blue chips.”

For sports card investors who aren’t blessed with a scout’s eye for talent or a millionaire’s deep pockets, there’s another strategy to make money quickly. They emulate day traders by buying and selling cheaper cards quickly in an effort to capitalize on short-term price upticks.

Eighteen-year-old Kunal Ahuja was making some quick cash flipping sneakers until a little over a year ago when a friend told him about an even more profitable market. Ahuja’s friend said he had doubled his money in a month buying and selling sports cards.

“That really turned my head,” Ahuja said. “I sold off every shoe I had and put all that money into cards.”

Ahuja has invested in more than 100 players, buying cards at the lowest prices he can find in a surging market and then quick-flipping them after a strong playoff series or a three-touchdown performance. It’s a time-consuming process for the full-time student, but Ahuja estimates he has made more than $50,000 from his own investments and a subscription program in which he offers recommendations to members

“If you’re an investor and you see the numbers sports cards have done, it has to get your attention,” Ahuja said. “If you have knowledge in sports, there’s money to be made here.”

Of all the evidence of how hot the sports card market is these days, the most striking might be that investors don’t even need to open packs or boxes of high-end cards to turn a profit. Demand for new inventory is so high that they can usually resell them for far more than the manufacturer’s suggested retail price.

Cory Buchanan was shopping in a Sacramento-area Walmart last month when he stumbled across a goldmine. The store had just restocked its sports card section with 12 boxes of Bowman Chrome baseball cards.

“They were $35 apiece and I bought all of them,” Buchanan said. “I came home with a full bag. My fiancee thought I was nuts.”

Buchanan’s fiancee was a little more understanding after he shared his profits with her. He sold four boxes on eBay overnight for more than double what he paid and peddled six others at $70 apiece to a nearby sports card shop.

To Buchanan, the thrill of the hunt is as appealing as the quick money. He now notes in his phone what days Sacramento-area retailers restock their sports cards and tries to time his visits to nab as many packs or boxes as he can find.

Whatever money Buchanan makes, he usually puts right back into the hobby. He has invested a couple thousand dollars into newly crowned American League rookie of the year Kyle Lewis, Tampa Bay prospect Wander Franco and 22-year-old Braves sensation Ronald Acuña Jr.

“I like to be able to find the next big thing,” Buchanan said. “Am I going to strike out on a couple of these guys? Of course. But that’s the risk you take.”

Is this just another bubble ready to burst?

The lingering question on the minds of most sports card investors is how long they should plan to stay in this space.

Could the second sports card boom have more staying power than its predecessor? Or should savvy investors be looking to cash out quickly before interest wanes, prices plummet and the latest cardboard craze goes bust?

Dave Oancea is a pessimist. Pouring more money into expensive cards is one risk the sports gambler won’t take.

With cards featuring less accomplished players selling for more than the $400,000 he paid for the Trout Superfractor two years ago, Oancea predicts that the market is nearing its peak. In two or three years, he envisions the sports card bubble bursting and values nosediving.

“Get out now while you still can,” he warned. “You’re going to lose your asses if you don’t.”

Geoff Wilson isn’t so paranoid. As long as card manufacturers have learned their lesson about the perils of overprinting and the importance of scarcity, the tech entrepreneur and founder of Sports Card Investor sees signs the industry has entered a run of extended prosperity.

Attendance at the most recent pre-pandemic National Sports Collectors Convention was as high as it has been since the industry’s early 1990s heyday. New Instagram accounts and YouTube channels devoted to sports cards seem to pop up every day.

Hedge funds, venture capitalists and pools of investors are entering the sports card market armed with big bucks and big ideas. There’s even a real estate-inspired startup on its way that will sell shares of particularly expensive sports cards to investors who dream of owning them but otherwise could never afford them.

“I’m absolutely bullish on the growth of the market,” Wilson said. “I think we’ve got a great run ahead of us. Sports cards are a rocket ship right now. And they’re a rocket ship that I’m very glad I’m sitting toward the front on.”

One more encouraging sign for the sports card industry is the celebrities who are starting to show interest. This week, Rob Kardashian gave owners of a Los Angeles sports card store permission to livestream the opening of a case of football cards he purchased and national headlines followed because of a valuable one-of-a-kind Tom Brady card they pulled.

It’s Pruser’s hope that stories like that will help introduce sports cards to a wider audience and keep the market strong for another decade. By then he intends to have sold off his Kershaw collection and his stockpile of other valuable rookie cards, nudging him closer to his goal of retiring by age 50.

“When you tell people you have more than $1 million invested in baseball cards, they look at you funny, but it’s paid off,” Pruser said. “I’m in a position now where I can continue to sell, lock in profits and be comfortable for the rest of my life.”

More from Yahoo Sports: